Home » Minerals » Legal Aspects of Rock Collecting

Part 2: Determining Rock, Mineral, or Fossil Ownership and Possession

Deeds are legal documents that detail the ownership of property or rights.

So how does a rock, mineral, or fossil collector figure out who owns particular specimens of interest and from whom permission may be needed? The answer would likely be found in a number of different legal documents and relationships, a non-exhaustive list of which is provided below.

ADVERTISEMENTDeeds are of primary importance in determining the ownership of land and the rocks, minerals, and fossils located on it. Despite the various types (e.g., general warranty, special warranty, quitclaim) and names (e.g., deeds, indentures), these documents transfer and evidence ownership of property and are usually recorded in the local courthouse or public records repository. For anyone, not the least of which are collectors, looking to determine the legal owner of property, the information in the current, most recent deed may quickly and easily contain the answer by clearly identifying who owns the property. Deeds must describe the property owned and being transferred in some manner and, therefore, should identify whether ownership includes the surface land or some other mineral or stone interest. 9 In some cases, deeds evidencing ownership of the surface land will also expressly indicate that ownership includes the mineral or stone interests in the property as well. In many cases, however, deeds evidencing ownership of the surface land will also do the opposite; they will expressly indicate that the mineral or stone interests in the property were previously transferred, removed, or severed (oftentimes referred to as being "excepted," "reserved," or "retained") and now belong to someone else. In many cases, deeds for surface lands do not clearly indicate that someone else owns the mineral or stone interests. In those cases, a collector would only be able to confirm who owns the mineral or stone interests by performing or obtaining what is called a "title search" on the property. A title search on the property typically includes a review of prior recorded documents and identifies the current owner of the mineral or stone interests based on those documents. 10 The specific language within a deed and the interpretation of that language may also be determinative of ownership or possession rights to particular specimens. For example, a deed transferring ownership of mineral and stone interests may or may not generally cover surface rocks depending on the specific wording used. 11

Vial of gold flakes typical of what might be found by an amateur prospector. The gold in this vial would easily be worth hundreds of dollars. Removing it from private land would be theft - unless you have permission. However, if you are in compliance with government regulations, you would be allowed to keep it, if found on many Bureau of Land Management properties. BLM image.

Leases are similar to deeds in many respects. In some cases, legal documents that function more like deeds in transferring legal ownership of mineral or stone interests are actually called leases. In most cases, however, leases only give someone a right to possess and use property for a particular purpose and for a limited duration. 12 For example, a property owner might lease mineral interests to a mining company, enabling the mining company to enter on the land to mine and take out minerals for ten years. The mining company would not own the surface land and may not own minerals that it does not mine and that remain in the ground or on the property. As with deeds, the specific language within a lease agreement and the interpretation of that language may affect ownership or possession rights to particular specimens.

ADVERTISEMENTEasements and conservation agreements generally transfer an even more limited interest in property. These legal documents are intended to limit the use of the land in order to conserve its natural state. Oftentimes these conservation easements and agreements are granted to non-profit and government agencies with the goal of environmental protection and natural resource conservation and preservation. Accordingly, any use that is inconsistent with conserving land in its natural state are severely restricted or altogether prohibited. For example, conservation easements may permit hiking and other recreational activities, but would likely prohibit mining, quarrying, and, in some cases, even farming. Rock, mineral, and fossil collectors must keep in mind, however, that a conservation easement granted for the surface of land may not cover or be applicable to mineral or stone interests in the property that were previously transferred to another person. In instances where conservation easements and agreements are in place, the entity receiving the easement or agreement to ensure conservation controls the use of the property, including its use for specimen collecting.

| This Stuff Really Happens! |

Land patents and warrants establish someone's right and interest in land previously owned or controlled by the government. In the American legal system, governments assumed initial ownership or control of land that was considered otherwise unowned and unclaimed. In order to incentivize the use and development of such vacant land, oftentimes for homesteading and ranching purposes, governments offered to grant patents and warrants for finite portions of that land to persons who satisfied certain requirements (usually related to occupying and developing that land). In cases where lands are still subject to patents and warrants and, in particular, for which no deed has ever been issued, those patents and warrants establish ownership and possession rights for those surface lands. Consequently, land patent and warrant holders would, therefore, hold ownership and possession rights for specimens on those surface lands. Many such patents and warrants, however, contain reservations to the government for the mineral and stone rights for those lands. Thus, the government would retain the ownership and possession rights for subsurface rocks and minerals. Additionally, prior to 1994, many other patents were issued specifically for mineral interests in property, thereby transferring to those mineral patent holders ownership and possession rights for subsurface rocks and minerals. While it is not impossible to happen across property still subject to a patent or warrant in the eastern portion of the United States, patents and warrants are much more common in the western regions of the country as a result of more limited development and various congressional acts to promote the use and development of the large expanses of land in those areas. In cases where property is subject to neither a deed nor a patent or warrant, the federal government typically holds control and possessory rights to such property.

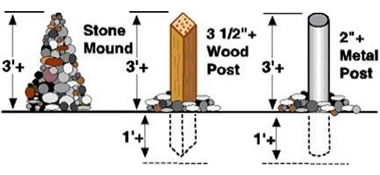

Recognizing a mining claim in the field: Mining claims are required to be marked by conspicuous and substantial monuments. If you see stone mounds, wooden stakes, or metal posts in the field, they could be on the boundaries of a mining claim. The person who holds a mining claim has the exclusive right to develop and remove materials from the site. These areas should be avoided when you are searching for rock, mineral or fossil specimens. BLM image.

Here, someone has used a wooden stake to mark their mineral claim. BLM image.

Mining claims are granted on federal lands for mining locatable minerals under the General Mining Law of 1892. Mining claims require that persons locate and claim areas with valuable mineral deposits for mining purposes by following identification and location criteria and other management requirements mandated by the federal government and administered by the Bureau of Land Management. 13 Someone with a mining claim has possessory rights limited to developing and extracting the claimed mineral deposit. Those possessory rights could include rocks and other specimens located on either the surface or subsurface of the land. A person holding a mining claim does not own the land subject to the mining right, which in most cases continues to be held by the federal government. 14

After determining who owns or possesses the rocks, minerals, or fossils in question, a collector should try to determine from whom permission or consent is needed. Obtaining sufficient permission or consent for collecting involves two requisite components: 1) approval to enter onto the land to search for rocks, minerals, and fossils; and 2) approval to take the specimens. With both of these permissions, the rock, mineral, or fossil collector will not be trespassing, stealing, or a running afoul of a number of other crimes and civil wrongs.

Unfortunately, determining from whom permission or consent should be sought can become complicated. If an individual person is the title owner or possessor of the rocks, minerals, or fossils, it may be as simple as contacting that individual person and requesting permission to enter on the land and collect specimens. What if, however, multiple individuals are identified as the joint owners or possessors of the specimens? What if a company, nonprofit organization, or government or governmental entity is determined to be the owner or possessor?

ADVERTISEMENTIn most states, where property is owned jointly, permission or consent to enter upon the property to search for rocks, minerals, and specimens in a non-damaging and non-invasive manner need only be given by one joint owner. Likewise, permission to take a few small specimens of little value would likely only need to be granted by one of the joint owners. If, however, the search for rocks, minerals, or fossils would be damaging or invasive, or rocks of substantial value or volume are to be taken, permission from all joint owners would likely be appropriate or legally required.

Where a company, nonprofit organization, government, or governmental entity owns or possesses the property, permission or consent should be sought from an authorized representative, officer, or employee of the owner or possessor. In most cases, officers and management-level employees have the authority to grant permission or consent. In many other cases, other administrative employees may have been given the power to grant permission or consent as well.

Government lands present interesting questions regarding permission and consent to collect rocks, minerals, or certain fossils. In many cases, government lands are administered by particular governmental agencies. Oftentimes, for public lands, these governmental agencies are park or forest services. For federal lands, the most significant governmental agencies are the Bureau of Land Management, the United States Forest Service, and the National Park Service. For many of these governmental agencies, formalized procedures have been adopted and implemented for making requests to enter and collect specimens. Likewise, specific local branches of these governmental agencies have been given the authority to grant needed permissions in accordance with their management and administration responsibilities. 15

Rock, mineral, and fossil collectors should note that in many instances, permission to enter upon public lands to search for specimens is implied and no additional permission is necessary or must be specially requested (e.g. national and state parks). 16 Simply because someone has implied permission to enter public lands does not, however, mean that the collector also has permission, implied or otherwise, to search for rocks, minerals, or fossils in a damaging or invasive manner, let alone to take or remove specimens from those public lands. Collectors should confirm whether implied permission or consent to take or remove rock, mineral, or fossil specimens has also been given as well. In many cases, applicable laws and regulations specifically prohibit removing rocks and other specimens from government lands. 17 If implied permission or consent to take or remove specimens has not been given, collectors should specially request that permission. These same legal principles also apply to private lands subject to public recreational use under various laws. 18 Even where permission or consent to enter upon private lands for recreational purposes, including searching for specimens, is implied, specific permission to actually take or remove rocks, minerals, or fossils should still be sought from the private land owner or possessor.

One particularly important example of there being permission to search for specimens but not permission to remove them is government land administered by the National Park Service. On such lands, federal law prohibits possessing, removing, gathering, or digging rocks and other specimens without a necessary, restricted permit. 19 Typically these permits are limited to scientists and researchers who are permitted to collect and take rocks and other specimens subject to substantial conditions. Indeed, in recent years, stealing rocks and other specimens has become recognized as a problem in some parks, like Acadia National Park, that additional rangers have been hired to catch thieves. 20

ADVERTISEMENTRock collectors should also note that permission or consent may need to be obtained from multiple people. As described earlier in this article, it is not uncommon that the surface land and the mineral or stone interest associated with a particular property are each owned or possessed by different people. Accordingly, permission should be obtained from anyone whose rights would be affected by the anticipated rock, mineral, or fossil collecting activities.

Understanding the gravity and importance of permission or consent (and the potential negative consequences of failing to obtain it), rock, mineral, and fossil collectors may ask how best to protect themselves. Do they need to obtain formal permission or consent in writing? While written permission affords the strongest protection against being charged with a crime or being sued civilly, it is, admittedly, impractical or might come across as unseemly to request written permission in certain instances. Imagine wanting to collect rocks on the land of a friendly elderly gentleman who happens to be a friend-of-a-friend. He could be offended or become unnecessarily reluctant or apprehensive if asked to provide written permission. Accordingly, in many instances, particularly where property is owned by individual persons, obtaining written permission is not crucial. Instead, obtaining verbal permission will oftentimes be sufficient protection against being charged with a crime or being sued civilly. Collectors should, nonetheless, note from whom and when permission was obtained. In other instances, obtaining written permission may be highly recommended or even required. For example, rock collecting activities on certain government land must be approved through a formal permitting process from which a written permit is issued; collecting rocks on those government lands without the necessary written permit is illegal. Similarly, written permission should oftentimes be obtained, as a practical matter, when entering or collecting on land owned by companies or organizations where the representatives that grant permission for rock, mineral, or fossil collecting activities are not the same representatives that monitor or patrol the land. Being able to produce written permission, upon request, in such situations generally avoids misunderstandings, awkward situations, and potentially dangerous confrontations. In some cases, written permission is required by certain laws even when verbal permission has been given by the landowner. For example, under Pennsylvania's Cave Protection Act, it is unlawful for someone to remove or take rocks and other specimens from a cave without the express written permission of the landowner. 21

Part 2: Determining Rock, Mineral, or Fossil Ownership and Possession

| Timothy J. Witt is an attorney with the firm of Watson Mundorff, LLP. He can be reached by email at This article does not provide legal advice and does not create an attorney-client relationship. If you need legal advice, please contact an attorney directly. |

| Footnotes |

| ^ 9 There are other types of property interests beyond those mentioned here. Oftentimes, these property interests can be very complicated and rely on very specific wording or legal terminology. Unfortunately, these other types of property interests are more uncommon and esoteric. Therefore, the inclusion of a discussion about them in this article would be cumbersome and substantially lengthen and complicate this article. |

^ 10 Determining legal ownership or possession can be hard enough as it is, but the challenge presented by unrecorded documents presents an even greater difficulty. An unrecorded document, although generally bad practice, may validly transfer ownership or possession of rocks or land to someone else, but there is no conclusive way of finding or verifying such transfers. Thankfully, the existence of unrecorded documents is fairly uncommon and can present even thornier legal issues for the true owner or possessor. Unrecorded leases, although still uncommon for large tracts of unimproved land, likely present the most significant challenge for determining legal possession.

^ 11 Two such recent examples are found in Pennsylvania. In one case, an owner reserved "all the oil, natural gas, glass sand and minerals of every kind and description whatsoever, together with the rights of egress, ingress, and regress into, upon and from the same at all times for the purpose of exploring, operating for, producing, storing and transporting the same." PAPCO, Inc. v. United States of America, 814 F.Supp.2d 477, 481 (W.D. Pa. 2011). In that case, the court concluded that the owner reserved ownership of sandstone located on the surface and was permitted to surface mine such sandstone. In another case, an owner reserved "all coal and other minerals beneath the surface of said described land, with the right to mine and remove the same by subterrane mining." Vosburg v. NBC Seventh Realty Corp., 122 A.3d 393, 395 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015). In that case, the court concluded that that the owner had not reserved ownership of stone located on the surface and the surface owner was permitted to collect and use stone on or near the surface. These sorts of cases underscore the importance of closely examining the language used in deeds and other documents regarding land ownership and use.

^ 12 Leases on federal lands granted under the Minerals Leasing Act, 30 U.S.C. § 181, et seq., as amended, would also fall into this category. Additionally, sales and permissions granted under the Materials Act of 1947, 30 U.S. Code § 601, et seq., as amended, are comparable to leases of limited duration despite being outright sales of mined materials.

^ 13 For an excellent explanation of federal patents and mining claims, see Cantley, Beckett G., "Environmental Protection or Mineral Theft: Potential Application of the Fifth Amendment Takings Clause to U.S. Termination of Unpatented Mining Claims," 4 Wash. & Lee J. Energy, Climate, & Env't. 203 (2013).

^ 14 There are instances of lands the surface of which are privately owned under the Stock Raising Homestead Act of 1916, but the subsurface of which is subject to mining patents and claims pursuant to special procedures (43 CFR Part 3838).

^ 15 See e.g. 43 CFR 8365.1-6. "Supplementary rules. The State Director may establish such supplementary rules as he/she deems necessary. These rules may provide for the protection of persons, property, and public lands and resources. No person shall violate such supplementary rules.

(a) The rules shall be available for inspection in each local office having jurisdiction over the lands, sites or facilities affected; (b) The rules shall be posted near and/or within the lands, sites or facilities affected; (c) The rules shall be published in the Federal Register; and (d) The rules shall be published in a newspaper of general circulation in the affected vicinity, or be made available to the public by such other means as deemed most appropriate by the authorized officer."

See e.g. 43 CFR 3622.4(b). "Additional rules. The head of the agency having jurisdiction over a free use area may establish and publish additional rules for collecting petrified wood for noncommercial purposes to supplement those included in paragraph (a) of this section."

^ 16 See e.g., 14 CCR § 4307(b): "Rockhounding may be permitted as defined in Section 4301(v)."; 14 CCR § 4611(b) Units and portions thereof open for Rockhounding will be posted in accordance with Section 4301(i)." Rock collectors should also note, however, that despite this implied authorization, rock collecting is still prohibited in otherwise permitted areas that are "designated for swimming or boat launching" or, conversely, is limited to "beaches which lie within the jurisdiction of the Department and within the wave action zone on lakes, bays, reservoirs, or on the ocean, and to the beaches or gravel bars which are subject to annual flooding on streams." See 14 CCR § 4611(f), (g).

^ 17 For example, the disturbance or removal of rocks and specimens on government lands administered by the Army Corps of Engineers would appear to be prohibited without written permission. See e.g., 36 CFR 331.6: "Public property. Unless otherwise authorized in writing by the District Engineer, the destruction, injury, defacement, removal, or any alteration of public property including, but not limited to natural formations, paleontological features, historical and archaeological features and vegetative growth is prohibited. Any such destruction, removal, or alteration of public property shall be in accordance with the conditions of any permission granted." Rules applying to lands of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources provide a similar and clear example on the state level. See e.g., 312 IAC 8-2-10 Preservation of habitat and natural and cultural resources: "Except as authorized by a license, a person must not do any of the following within a DNR property: (5) Damage, interfere with, or remove: (C) a rock or mineral; (10) Dig or excavate any material from the ground." In Utah state lands governed by the School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration require a permit for even recreational rockhounding, while lands administered by the Utah Department of Natural Resources are closed off from rock collecting. See e.g., Utah: R651-620-2. "Trespass. (1) A person may be found guilty of a class B misdemeanor, as stated in Utah Code Annotated, Section 79-4-502 if that person engages in activities within a park area without specific written authorization by the division. These activities include: (b) removal, extraction, use, consumption, possession or destruction of any natural or cultural resource."

^ 18 One such example is "agricultural reserve" land that is required to be open to the public for recreational purposes under the Pennsylvania Farmland and Forest Land Assessment Act (Clean and Green Act) and its accompanying regulations. See e.g., 7 Pa. Code § 137b.64: "Agricultural reserve land to be open to the public. (a) General. An owner of enrolled land that is enrolled as agricultural reserve land shall allow the land to be open to the public for outdoor recreation or the enjoyment of scenic or natural beauty without charge or fee, on a nondiscriminatory basis." See also e.g., Pennsylvania's Recreational Use of Land and Water Act, 68 P.S. § 477-1, et seq. and Wisconsin's Managed Forest Law, Wisconsin Statutes § 77.80, et seq., (both providing for certain recreational uses of private lands, although not expressly permitting the taking or removal of rocks or specimens).

^ 19 See e.g., 36 CFR §§ 2.1 and 2.5. "Collecting, rockhounding, and gold panning of rocks, minerals and paleontological specimens, for either recreational or educational purposes is generally prohibited in all units of the National Park System. Violators of this prohibition are subject to criminal penalties." Two exceptions include limited recreational gold panning in the Whiskeytown unit of the Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area in California and hand collecting in some National Park Service units in Alaska. See 36 CFR §§ 7.91 and 13.20(c).

^ 20 Another interesting phenomenon is the return of "conscience rock" to national parks. "Conscience rocks" are specimens that weigh on the conscience of the taker who knows the illegality of taking those specimens. As an interesting aside, some people believe that taking rocks and other specimens from certain national and state parks, like Gettysburg National Military Park, carries a curse and results in misfortune and bad luck. See e.g., https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2016/07/07/cursed-rocks/.

^ 21 32 P.S. § 5605: "It shall be unlawful for any person, without the expressed written permission of the land owner, to: (1) Willfully or knowingly break, break off, crack, carve upon, write, burn, mark upon, remove or in any manner destroy, disturb, mar or harm the surfaces of any cave or any natural material which may be found therein, whether attached or broken, including speleothems, speleogens and sedimentary deposits…(7) Remove, deface, tamper with or otherwise disturb any natural or cultural resources or material found within any cave [or] (8) Disturb or alter in any way the natural condition of any cave."

| More Minerals |